The first time Michael Schreffler visited the Peruvian city of Cuzco, he noticed the architectural legacy of the Inca civilization still standing next to buildings that represent the European Baroque style.

The visual contrast tells part of the story of Spanish colonization.

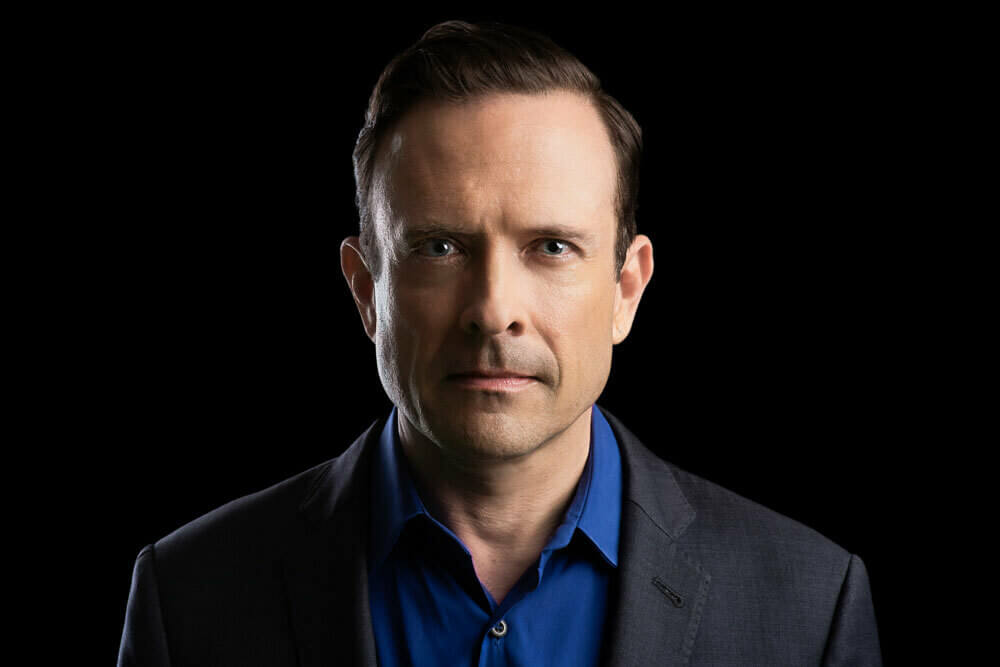

“In a way, it’s like Rome, in that you see the layers of history — multiple periods of history through architecture that is still visible,” said Schreffler, a Notre Dame professor of art history and the College of Arts & Letters’ associate dean for the arts. “Why do you see so much of that in a city that was invaded and settled by the Spanish 500 years ago?”

Schreffler’s first trip to Cuzco 21 years ago — and about 10 subsequent visits — provided the spark for his 2020 book, Cuzco: Incas, Spaniards, and the Making of a Colonial City, which has now won the Spiro Kostof Book Award from the Society of Architectural Historians.

The award is named for a University of California, Berkeley professor who served as president of SAH in the 1970s. Kostof’s interdisciplinary research was considered novel at the time. He wrote about cities’ infrastructure and architecture, while also informing readers about their settings for human interaction and ritual practices.

“That is the approach I took in my book, so I’m grateful for this recognition named for a person who broke ground in this field,” said Schreffler, who received the honor at a ceremony this month in Montreal. “It validates doing this kind of work and makes me excited that other people who read the book found it interesting and were able to connect a bigger world of ideas to the history of architecture.”

Schreffler’s book addresses how Cuzco transformed after the Spanish invasion in the 1530s. Today, the city is best known as the place where tourists spend time before traveling to Machu Picchu.

While previous research has covered the overall Spanish conquest of Peru, Schreffler wanted “to take a look at that story from the vantage point of one city, arguably the most important city in the Inca Empire in this period,” he said.

The city didn’t experience the destruction seen elsewhere — beautiful, distinctive stone carvings and other examples of Inca architecture remain, while Aztec architecture in Mexico City was erased.

The key, he said, was the way space was repurposed in Cuzco while its cultural reality was forever changing.

“When I teach this material in my classes, I like to ask students, ‘What can we say about long-term consequences of Spanish colonialism in a place like this?’ One of them has to do with the social dimensions of geography. The Spanish government established itself in Lima while Cuzco and its environs were populated largely by Quechua-speaking Andean peoples,” he said, referencing the language of the Incas.

“The social inequalities in Peru today and, in particular, discrimination against speakers of Quechua has its origin in the colonial period. But the visible remains of Inca architecture in Cuzco remind us that the city’s transformation over time is not simply a story of loss. It is also a story of resilience.”

“I’m grateful for this recognition named for a person who broke ground in this field. It validates doing this kind of work and makes me excited that other people who read the book found it interesting and were able to connect a bigger world of ideas to the history of architecture.”