James Rudolph’s creative exercises can be measured in movement.

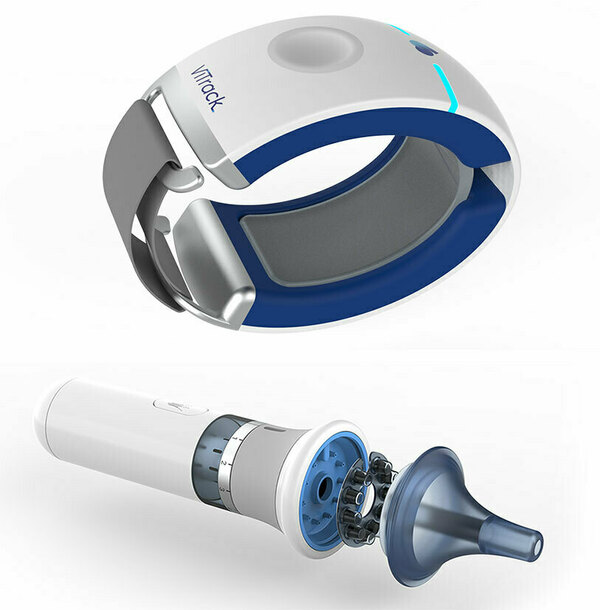

Surgical robots make precise actions to replace knees and hips. A handheld device determines whether cancer treatment is working without breaking the skin. A spinal cord is repaired with a surgical instrument that is less invasive to the patient.

The medical devices Rudolph designs move so people can focus on moving forward.

“I’m fortunate enough to work on projects that can have lasting, meaningful, positive impact on peoples’ lives,” said Rudolph, an assistant professor of industrial design in Notre Dame’s Department of Art, Art History & Design. “The goal is discovering important problems and trying to understand insights that would lead to better futures.”

Rudolph maintains this mindset in the classroom, where the same concepts that create breakthrough medical robots can be replicated by students who are designing everything from marketable products to physical environments to artistic experiences.

The foundation of Rudolph’s work is an examination of an individual’s behaviors, values, needs, wants, and decision-making process. Impactful design solutions arise in a process that flows from immersion, ideation, refinement, and implementation.

“My focus is human-centered design,” he said. “Really, it’s to create more successful interactions and user experiences so they are safer, more efficient, and more enjoyable.”

“When I was a design student, I knew I wanted to do something that would have a bigger meaningful impact. With a major in design, you can go into furniture, gaming, footwear, electronics. I knew, very early on, I wanted to do something that had a positive impact on people’s lives.”

Meaningful impact

Rudolph arrived at Notre Dame in 2019 after an industry career that began at Farm Design in New Hampshire, where he focused on creating healthcare products and services. There, he collaborated on projects to develop orthopedic aids and surgical robots, conducted field-based ethnography to interact with users of the equipment, and served as a project manager overseeing the work of researchers, designers, and engineers.

Rudolph worked on one of the first surgical robots that is currently used for orthopedic procedures, such as knee and hip replacements. He also helped develop a system that can non-invasively destroy cancerous tissue in the liver, stomach, and other primary organs.

“When I was a design student, I knew I wanted to do something that would have a bigger meaningful impact,” he said. “With a major in design, you can go into furniture, gaming, footwear, electronics. I knew, very early on, I wanted to do something that had a positive impact on people’s lives.”

These days, in addition to his work at Notre Dame, he runs Rudolph Design Studio with his wife, Morgan, and is contributing to several projects in varying stages of development:

- A startup company formed by Notre Dame students and professors is creating a hand-held device that will determine the efficacy of chemotherapy treatments for breast cancer. The device uses near infrared light to examine tissue density, and if the chemotherapy isn't working, the exam results inform the doctor and patient to change treatment course.

- A group at MIT is creating a device to accurately measure blood pressure in a continuous, accurate, and non-invasive way during a surgical procedure.

- A nascent healthcare company is developing a way for people with chronic kidney disease to conduct hemodialysis at home, eliminating the need for three or four trips to a clinic each week.

- An established medical device corporation is working to develop an advanced robot to assist with spine surgery.

With any research and design project, Rudolph is consistently communicating — with people who will use the new device and, perhaps most importantly, with the people who would benefit from it.

“It’s just listening to their stories and giving them the opportunity to talk about their experience. I’ve spent a lot of time in operating rooms and people’s homes, especially with elderly folks who love to tell stories,” he said. “You go along with them when they want to show you their wedding photography equipment from the 1950s. You give them the time because they appreciate it, and they want to help.”

Immersion is the first step of his creative problem-solving process. He studies the space that the problem exists in, and he seeks to understand the people and their needs. He also must review the technology already in existence.

The process then moves to ideation, where a strategy is designed to solve the issues identified during immersion. New ideas emerge, and prototypes are created and evaluated to ensure the right problem is being solved.

During the next stage of refinement, the team dives into the design and the details. They decide what features are included and which are left out. The final stage is implementation, and the design is engineered for production.

“We’re trying to get people the result they want in the easiest way,” he said, “often in the space where you’re combining really important healthcare challenges with these new pivotal technological breakthroughs to provide more effective, efficient, safer healthcare solutions.”

“We’re trying to get people the result they want in the easiest way, often in the space where you’re combining really important healthcare challenges with these new pivotal technological breakthroughs to provide more effective, efficient, safer healthcare solutions.”

Fresh perspective

Since joining the Notre Dame faculty, Rudolph has found that the operational structure he worked with in the industry — the environment that fosters quality research, design, engineering, and project management — correlated strongly to the process of organizing a curriculum and guiding student projects.

And there’s much more to design than technique and aesthetics — developing research skills in applied ethnography is also essential.

One course Rudolph teaches involves a collaborative effort with corporate partners to help students understand the principles and practice of design research methods. The approach uncovers latent and tacit needs that people may not be able to verbalize until they talk with the students.

Last spring, the class partnered with Lippert, an Indiana manufacturer of recreational vehicle components, to create a better camping experience for RV enthusiasts who use motor homes or tow-behind campers. Rudolph worked with Notre Dame’s iNDustry Labs, which catalyzes and stewards University collaborations with the region’s manufacturers, to launch the course.

The students conducted their work in three phases: immersion with RV owners, sensitizing exercises that helped them gain understanding of the participants’ experience, and generating new concepts based on what was identified as important to the participants.

The students quickly learned that RV owners have a sense of pride in their vehicles, which they view as a second home capable of providing the freedom to travel and meet people they otherwise would never encounter. The students learned that, for RV enthusiasts, the relationships are as much the destination as the campground itself.

So the students designed a park that places the RVs in a series of circular pods that create one big circle for the community. This approach avoids a layout of rows that aren’t as conducive to community gathering.

The students’ design allows for shared kitchen, grill, and dishwashing spaces that bring everybody together in the view of others.

“These were all ideas prompting icebreaker-type activities to naturally meet people,” Rudolph said. “They also identified the importance of a ‘town crier’ who can tell people about events that might be happening for socialization and integration into the community.”

Lippert, the corporate partner, valued the research insights so much that it plans to use them as it partners with campgrounds to test new technologies and services. It also wants to work with Rudolph’s students on a new project every year — this semester, the class has expanded the focus to include water-based recreation, and will employ similar research exercises with boaters.

Focusing on products and experiences the students are unfamiliar with doesn’t just increase the amount of research they have to do — their outsider perspective enhances the end result, as well.

“When you do things regularly, like biking, you become an expert and innately behave in certain ways. It becomes very natural, and you forget about the process and challenges you faced early on,” Rudolph said. “But if you apply research methods to a space you have no experience in, you have to approach it carefully and methodologically. For any research class like this, it’s much more educational if it’s a space students have little experience in.”

Fortunately, Rudolph is a guide with plenty of experience. And the movement — of people, products, and ideas — is sure to follow.