After she hit.

It’s been five years since Hurricane Maria devastated the island of Puerto Rico.

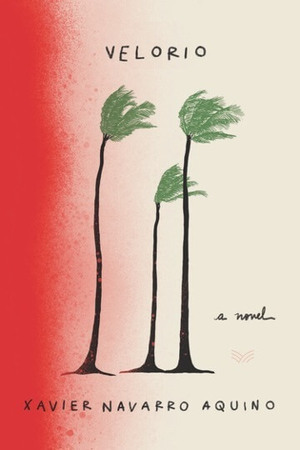

The grief, trauma, and political ramifications of this seismic event in the island’s history are skillfully rendered in Xavier Navarro Aquino’s new novel, Velorio.

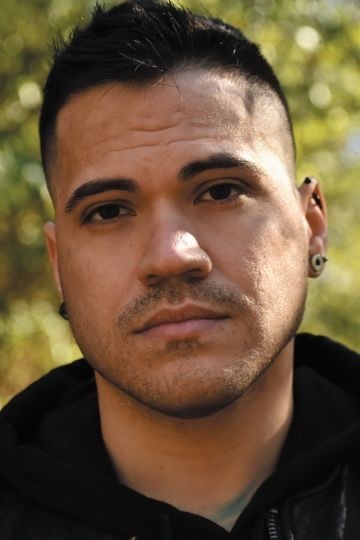

It’s a powerful debut for Navarro Aquino, an assistant professor of creative writing at the University of Notre Dame and a faculty fellow at the Institute for Latino Studies.

On Wednesday, the Institute for Latino Studies, in partnership with the Creative Writing Program, will be hosting a book launch and reading in room 232 of Decio Hall. A conversation with Professor Marisel Moreno of Romance Languages will follow.

"Velorio" translates to funeral wake, a vigil for the dead. Many of the novel’s characters labor under a sense of personal and collective bereavement. The varied cast includes fish mongers, university students, street peddlers, a grieving sister, and others trying to put together their lives after Hurricane Maria.

Meanwhile, from the mountains of central Puerto Rico, a shadowy leader promises a utopia to replace the “old government” — a new community called Memoria.

With his army of “reds” — orphaned children and teens playing the part of henchmen — self-anointed prophet Urayoán spreads the word to a population fed up with the corruption and ineptitude of their political leaders.

As a native of Puerto Rico, Navarro Aquino’s first-hand experiences on the island imbues his novel with intimate knowledge. His dive into the aftermath of Hurricane Maria through the eyes of a variety of local characters places readers directly in the mindset of survivors.

One way the novel presents Hurricane Maria is as “a sort of genesis, that instead of life, you're given death,” the author explains in a recent interview. The memory of Maria will never fully fade from the collective psyche. Instead, “everything moving forward for Puerto Rico will be marked by that natural disaster, hence a genesis.” As such, the island that both Navarro Aquino and his characters once called home is much changed compared to what it it is now.

One character, Camila, arrives in Memoria carrying the decaying body of her older sister Marisol, who was killed by a mudslide. The novel begins and ends by telling their story, a sustaining motif for how survivors must carry on the memory of their loved ones. The official death toll was around 3,000 people, though there continues to be controversy surrounding the count.

Undoubtedly, the novel serves as a political indictment of the ruling class of Puerto Rico and the United States, which has exercised control over the island since the Spanish-American War of 1898.

The novel positions the government’s response to Hurricane Maria as the latest example of colonialism dating back to the coming of Christopher Columbus five hundred years ago. It struggles with this inheritance and the way forward, particularly around the idea of nationhood and the use of public land for private gain.

Characters wait an eternity for basic food items and clean water at local Walmarts and grocery stores. Others survey seemingly endless lines at local gas stations they know will run out of fuel before their turn.

Barbs fly at “la Junta”, the fiscal control board set up during the Obama administration to address the billions of dollars in pension liabilities and other debt owed by Puerto Rico to outside lenders. Whitefish, a Montana-based government contractor awarded hundreds of millions of dollars to rebuild the electrical grid despite limited experience, is alluded to as an example of malfeasance.

“We got to mind that it was the fault of our leaders,” Moriviví, a university student, says in the novel. “As they yelled en el Capitolio and fed us the usual spin every four years, we wanted them to fall. How they tried concealing years of waste and corruption by paving roads with new asphalt during election years…We felt strong in adopting no colors; no red, blue, or green. We loved because there is no greater love than that for your home.”

The author explains that “home [his emphasis] means accepting nostalgia as a bias." And "trying to understand reality or new realities” is paramount throughout his novel and the struggles his characters face.

They “seek a home that no longer exists and can never be reclaimed.” However, this desire for what has been lost is not a wasted effort. Navarro Aquino views the attempted act of recreation by his characters as “part of an imperative to reconcile and move forward.”

Originally published at latinostudies.nd.edu.