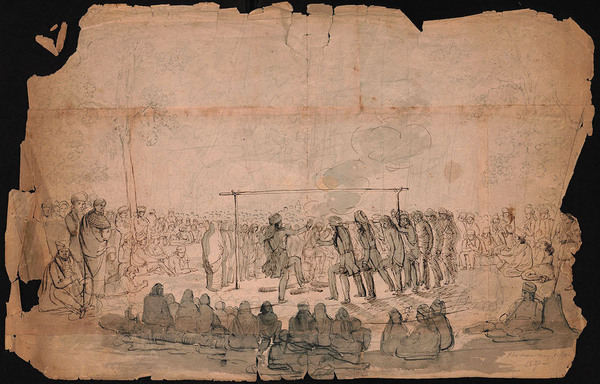

In 1837, when artist George Winter sketched a live Potawatomi dance social in northern Indiana, there was a consensus that Indigenous people would soon be extinct, said David Martin, a citizen of the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi, or Pokégnek Bodéwadmik.

“Native Americans as a whole, or the culture at least,” said Martin, the 2023-24 artist-in-residence with the Initiative on Race and Resilience in Notre Dame’s College of Arts & Letters. “In order for us to survive, we would have to become Americanized.”

One reason for the consensus was that U.S. officials were taking Indigenous children from their families and putting them in government- and church-run assimilation boarding schools.

Another was that U.S. soldiers were forcing Native Americans from their homelands in the East to land west of the Mississippi River.

“A lot of culture was lost,” Martin said. “Even in my lifetime, it was against the law for me to dance.”

‘We made it’

The Pokagon Band of Potawatomi ultimately proved the consensus wrong. Today, the federally recognized tribe has more than 6,000 citizens.

And more than 185 years after Winter sketched what some believed could be the last Potawatomi social in Indiana, Martin is helping to revitalize Potawatomi culture through the arts.

This fall, he organized and participated in two tribal dance and drum presentations on campus, one to celebrate Native American Heritage Month and another to mark the opening of the Raclin Murphy Museum of Art, where he is a member of the Indigenous Consultation Committee.

As IRR artist-in-residence, Martin also visits classes, opens his studio to students, supports the Native American Student Association, provides perspective as a working artist, and shares his culture, including through his paintings.

In his Riley Hall studio on campus, Martin works on his passion project — a 12-foot-by-6-foot oil on canvas that modernizes Winter’s sparse 1837 pencil drawing. One update includes changing Winter’s depiction of Indigenous people sitting on a log to tribal leaders relaxing in lawn chairs.

“Just to show that we survived. We made it,” he said. “We have issues that all minorities have, but we’re definitely on the upswing, and I want to represent that in this painting.”

Martin also updates tradition in his beadwork, other paintings, and tattoos.

“That’s my general philosophy. If you're a surviving, thriving, growing culture, you have to evolve to keep from becoming stagnant,” he said.

Understanding the past, though, is vital. And Martin is an educational resource on campus.

During a recent class visit, he noted to students that a novel’s period drawing of an Indigenous village in Chicago incorrectly included tepees.

“That’s not what it looked like in real life. We had wigwams and permanent log structures,” said Martin, whose Potawatomi name is Mamanjigosid Minosino.

Students sometimes ask him about a variety of topics, including Native American history.

“They can tell maybe they were taught something wrong, and they’re looking to correct it on their own accord,” Martin said. “If they ask me, I fill in the gaps. While I'm here, I’m just trying to humanize Native Americans to students and faculty who are not Native American.”

‘This is what we do’

Art has been important to Martin since his childhood — even before he recognized that beadwork and making Native American dance regalia were creative pursuits.

“Back then, almost everybody — you and your family — worked on outfits together,” he said. “And I thought, ‘This is what we do.’ It wasn’t until later in life I realized, ‘Oh yes, this is an art.’”

Martin’s work has earned acclaim in multiple mediums. His beadwork has been showcased at the Indiana Statehouse, South Bend Museum of Art, and the Snite Museum of Art, and his tattoos have won numerous national awards.

Martin learned to tattoo nearly 30 years ago; for the trained illustrator, it was a way to both support his family and remain involved with art.

“Our drum (drumming and dancing group) traveled a lot back then, in Oklahoma and Florida, so any time we went to a powwow, I tattooed Natives all night Saturday in my hotel room,” he said.

The former owner of Bicycle Tattoo & Piercing in South Bend also uses his talents for social good. While Martin hasn’t experienced discrimination directly, he said everyone around him has — including his children, who are Potawatomi and African American. In 2017, when white supremacists marched in Virginia, he and colleagues offered to cover up racist tattoos for free.

“It was the one thing we could do that was real and that could make an actual impact,” he said. “I think we really changed some lives.”

‘Dancing helped bring us back’

These days, Martin befriends people with opposing viewpoints, including those who argue that Native American mascots aren’t offensive. Martin even invited one such tattoo client to a powwow.

“It's easier to have a logical, friendly discourse if you’re friends first. It might be as simple as sharing food,” he said. “And now that we’re friends, he’s probably not comfortable calling my mom a redskin.”

Martin, who has a solo show, The Continuation Of The Potawatomi Culture, through March 24, 2024, at the South Bend Museum of Art, is continuing to work on his remake of Winter’s sketch of the Potawatomi dance.

“Winter recorded us dancing, thinking it was the end, that we were going extinct,” Martin said. “But over the years, dancing is almost universally what has helped bring Indigenous people back to their culture. I want to show that.”