Essaka Joshua has been elected a fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of London, an international educational organization that promotes understanding of the human past.

Founded in 1707 and issued a royal charter by King George II in 1751, the society supports conservation, research, and communication to advance understanding of history. Joshua was one of 13 people worldwide to receive the distinction; the group of new inductees also included Vice Admiral Sir Timothy Laurence — Princess Anne’s husband and chairman of a trust that creates inspiring experiences for visitors to England.

“Everybody needs some good news right now. It feels like I passed an exam I didn't know I was sitting,” said Joshua, a professor in the Department of English and a faculty fellow in the Nanovic Institute for European Studies, about being elected to one of the world’s oldest learned societies that connects her with 3,000 international scholars.

It comes with professional benefits, too — she can now use the post-nominal FSA (Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries), and she has access to considerable library and museum treasures. She’s already connected with several scholars and though she hasn’t yet visited the society’s headquarters at Burlington House in London, she’s attended online talks.

Joshua earned the accolade because of her expertise in myth and folklore, as demonstrated in her books, Pygmalion and Galatea: The History of a Narrative in English Literature and The Romantics and the May Day Tradition, which was shortlisted for the Folklore Society’s 2008 Katharine Briggs Award.

Her understanding of and appreciation for the human past has transformed and significantly deepened since her introduction to disability studies, which she’s researched for the past 20 years.

“I began re-reading texts and realizing that many of the historical terms used to describe disability — madness, idiocy, cripple, and even disability as a collective term — were culturally determined,” she said. “This perspective encourages us to ask why we assign these labels. This perspective means decentering able-bodiedness and able-mindedness.”

The evolving discipline of disability studies centers the experiences of people with physical, psychological and/or psychiatric differences who, like other oppressed groups, are marginalized because of exclusionary social structures and prejudices.

Disabilities, she said, are part of the human experience, not the exception.

“While disability may not be something you experience now, it is something that you or a family member or friend could experience at any time through accident, illness, or aging,” she said. “It’s imperative that we all think about the barriers to inclusion, whether that be physical, temporal, or prejudicial.”

“While disability may not be something you experience now, it is something that you or a family member or friend could experience at any time through accident, illness, or aging. It’s imperative that we all think about the barriers to inclusion, whether that be physical, temporal, or prejudicial.”

Dropping cultural filters

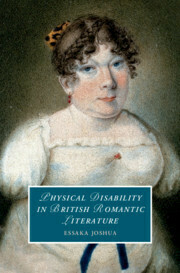

In her 2020 book, Physical Disability in British Romantic Literature, Joshua examined the understanding of equality and the evolution of ability/disability terminology at the end of the 18th century, when the modern concept of disability didn’t exist.

For the book’s cover, she chose a compelling self-portrait of Sarah Biffin, a celebrated 19th-century artist born without arms or legs who is referenced often in literature, including by Dickens.

“I wanted an image by a disabled artist of a disabled subject,” Joshua said. “As an artist without arms, she is unusual, and to paint on such a small scale a miniature of herself with her disability visible was remarkable.”

Joshua examines the intersection of disability studies and her other areas of expertise — Romantic-era and Victorian British literature, myth, and folklore — in a variety of engaging ways.

She’s a consultant on London-based Philip Mould Gallery’s exhibition of Biffin’s works, opening on Pall Mall in November. In addition to still lifes, self-portraits, and letters written by Biffin, the exhibition includes posters from a traveling circus in which Biffin used her mouth, teeth, and shoulders to sew and paint for the public. Joshua is also writing an essay for the exhibition catalog.

Joshua recently presented a paper at a conference on Dickens’ A Christmas Carol, analyzing whether Ebenezer Scrooge is neurodiverse, and she’s been invited to introduce curators at the Historic Royal Palaces to disability theory and history. She’s also contributing to a book that explores the relationship between the royal family and Shakespeare — her chapter is about disabled writer Mary Robinson, who acted in The Winter's Tale and was a reported mistress of George IV. She is also working on a chapter on disability, race and romanticism for another essay collection.

Joshua first became fascinated with the field of disability studies when she read Lennard Davis’ Enforcing Normalcy, which details prejudicial assumptions about what is “normal.” His description of the Venus de Milo, a statue without arms that’s held to be a symbol of beauty, resonated with her.

“Were we to see a real woman without arms, we might have a different reaction. We, in some sense, view the statue through a cultural filter,” she said. “It forced me to ask the question: ‘If I can look at a statue without arms and not see it as a woman without arms, then what else am I filtering?’”

A recognition of dignity

Joshua also creates opportunities for undergraduates to examine literature and life through a disability studies lens in her English literature course, Romantic & Victorian Disability, and in her College Seminar on Disability, which centers on a theory-into-practice approach.

“Teaching disability studies is important for establishing and confirming in students a recognition of the dignity of all human beings and is an important part of social justice and inclusive approaches to learning,” she said.

Joshua's College Seminar students learn to “audio transcribe” — using words to describe a movie or TV show’s key visual elements, including action, settings, facial expressions, and costumes — making them accessible for people who are blind or sight-impaired.

It’s challenging and enlightening for them to describe a comedy scene without giving away the punchline, or narrate the experience of the tango dance in Scent of a Woman in a way that doesn’t just list body parts. Plus, the American Council of the Blind’s audio-description guidelines insist on description rather than the interpretation, so students must also grapple with the problem of neutrality.

“They learn concision and the value and effect of word selection, think deeply about cultural translation, and about the relationship between image and text,” she said.

During the past two decades, Joshua founded the Disability Studies Forum, which supports disability awareness and encourages research on disability. She also won the Tyler Rigg Award for Disability Studies Scholarship in Literature and Literary Analysis, and conceived a stage production of Samson Agonistes, a play John Milton wrote when he was blind in 1671.

Joshua also recently joined the editorial boards of the Cambridge Studies in Romanticism book series and the journal PMLA. She is currently working on a book on disability in Romantic era theatre, and intends to combine her two fields of expertise with a book on disability and folklore.

While disability studies is Joshua’s latest academic interest area, folklore and poetry have captured her fascination since childhood. Joshua vividly recalls being spellbound at age 6 during a school assembly in Wales, in the United Kingdom, listening to the alliterative Old English poem Beowulf read aloud.

“I’ve never forgotten it,” she said. “Myth and folklore capture the imagination like nothing else.”