Students in Sara Marcus’ English classes march around the room to John Philip Sousa’s military songs, sing from a centuries-old score, and teach each other dance moves from West Side Story.

They also go on class trips to Tony Award-winning shows in Chicago and to local karaoke nights.

This might sound unexpected for a typical English class. But combining literary study with experiential learning is all in a day's work for Marcus, an assistant professor in Notre Dame’s Department of English.

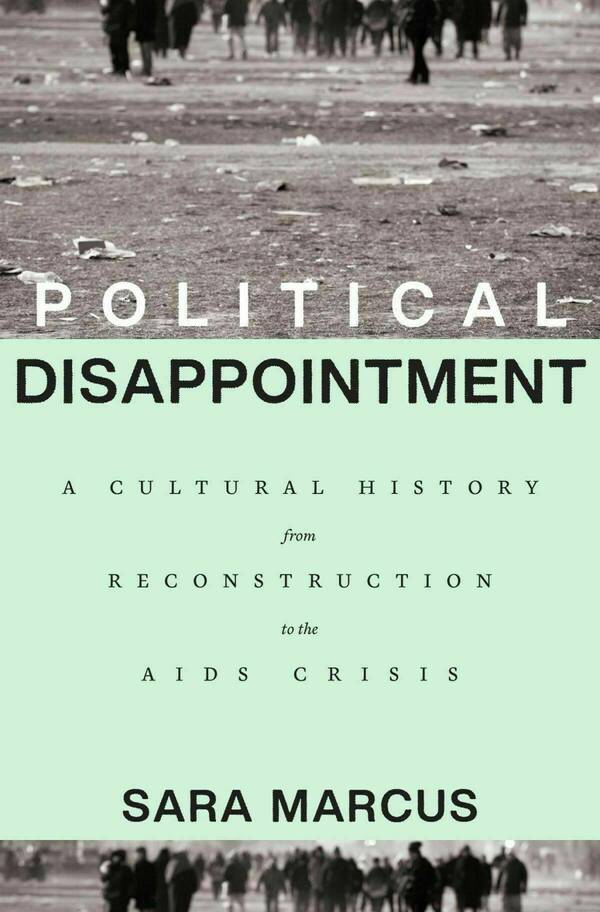

Her interdisciplinary research specializations include American and African American literature, popular music and sound studies, and gender and sexuality studies. Marcus is also the author of a new book, Political Disappointment: A Cultural History from Reconstruction to the AIDS Crisis, a similarly interdisciplinary project that has attracted major media attention and led to a multicity book tour.

In the classroom, Marcus often incorporates movement, theater, and music to bring the material alive and help students learn more effectively — and to have fun.

“I strongly believe that intellectual knowledge about a topic is always going to be deeper if there is an experiential dimension to that knowledge as well,” she said.

Making strides

The first time Marcus taught her course on American literature and popular music from 1860 to 1945, she realized that while some students (including Notre Dame marching band members) brought substantial musical experience to the class, others needed to build a technical vocabulary for talking about music.

So she devised exercises to help students speak and write about musical elements such as rhythm, meter, instrumentation, and compositional structure.

When learning about Sousa’s important role in small-town musical culture, for instance, students strode around the room to his military marches. They raised their hands above their heads when they heard the march’s first melodic theme and crossed their arms over their chests when they heard the second melody.

“We’re panting by the end of the song,” she said with a laugh. “It’s exhausting. But they really get it!”

Marcus said the activity helps students learn to listen analytically to a piece of music, identify its time signature, and notice when it changes from one section to another — essential skills for confidently discussing and writing about music.

In the course — which examined how racial politics, women’s changing roles, and mass commodity production influenced art between the mid-19th century and the end of World War II — students also used an 1835 shape-note songbook to harmonize “Amazing Grace.” The exercise enhanced discussions about the different ways people come to know things about sound, and it provided students with an understanding of how these hymnals made music accessible to amateur singers in early America.

In Marcus’ University Seminar course, Performance and Rebellion, first-year students each picked a dance move from West Side Story to memorize, then taught it to their classmates. Afterward, students identified how different movements conveyed specific feelings, such as exuberance, tension, and pride, based on how they themselves had felt when doing the dance.

“Instead of just watching the movement and talking about it, you're doing it yourself,” said Marcus, a faculty affiliate of the Gender Studies Program and the Initiative on Race and Resilience. “It's also a great trust-building exercise, because everybody is taking turns being vulnerable. In my teaching, I want to create a community where students support each other in sounding out the limits of their expertise and pushing beyond them.”

Patient attentiveness

Marcus was introduced to this approach to teaching as a doctoral student in English at Princeton University, where she was awarded a competitive scholarship in the Interdisciplinary Doctoral Program in the Humanities (IHUM).

“In IHUM, we each had to lead a participatory workshop on our research, and we were explicitly encouraged to experiment, to play around with format and method,” she said. “We were always asking: What is the widest range of practices we can bring to bear on our intellectual inquiries?”

The approach complements a patient attentiveness to aesthetic objects that is a signature of Notre Dame’s Department of English.

“In literary study, we commit to an honest account of what is actually in the poem, or novel, or story, or movie that we’re engaging with,” Marcus said. “We don’t leapfrog over the specifics and the material texture of our objects to talk about big ideas and political forces right away. We might get there eventually, but if and when we do, we’re ready to be responsible to our objects and understand how their complexity often defies easy instrumentalization.”

Marcus also thrives on observing the patterns, conversations, conflicts, and agreements during engaging class discussions.

“The most profound learning really happens when you work with others to collectively produce an understanding of a text or a concept rather than consuming it ready-made from someone else,” she said. “Classroom learning makes it possible to do things as a group that would be hard or even impossible to do alone.”

It’s a bonus that class discussions often inform her research.

“It’s a privilege to gather around a table with 14 to 16 extremely smart people and hear what they think about things. My students have great insights,” she said. “The questions they ask sharpen my own thinking.”

Disappointment and success

Marcus’ new book — Political Disappointment, published in May by Harvard University Press — details how writers and artists across the 20th century reckoned directly with political nonfulfillment in their songs, stories, documentaries, and more, and it argues that disappointment can serve as meaningful grounds for solidarity.

“Experiencing defeat is inexorably a part of laboring for a better community, nation, and world,” she said. “But recognizing this fact doesn’t have to be entirely depressing, because disappointment is proof of survival — it’s a mode of ongoing desire in search of new forms. My research shows it has also been incredibly generative, especially for people who confronted it head-on and came to understand its power to bring people together in new ways.”

The book has received significant national media attention, including reviews in The New Yorker, The Nation, and Bookforum.

“Marcus shows the ways in which Black activists and writers, in particular, have continued to express their political desires. In doing so, she draws our attention to the centrality of disappointment in American political life,” Princeton University professor Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor wrote in her piece in The New Yorker. “There is a fear of finality with failure, whereas Marcus is pulling her readers toward the continuity of desire for change.”

Thinking deeply and writing have been constants for Marcus, who wrote a book-length school project on world religions at the age of 11 and by high school was self-publishing articles about politics, literature, and music in the handmade magazines, or zines, that she made with friends.

More recently, she’s written reviews and essays for national media, including The New Republic and the Los Angeles Times.

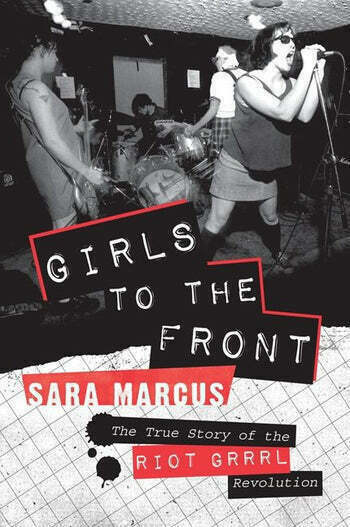

Music is another long-standing passion for Marcus, who started playing piano at age 4 and was part of the feminist punk Riot Grrrl uprising in her teens.

She’s played drums and keyboards in several bands, appeared in a documentary about the lead singer of Bikini Kill, and composed music for a klezmer-rock-opera version of the Yiddish play The Dybbuk. And she’s wrapping up a four-year term as associate editor of the Journal of Popular Music Studies.

If Marcus had time now, she’d start a band in South Bend.

“I know who in town I would have a band with; the fantasy lineup exists,” she said. “We just need to find a time to get together and jam.”

Grrrl to the front

Political Disappointment is Marcus’s first academic book, but it’s not her first book. She wrote Girls to the Front: The True Story of the Riot Grrrl Revolution (2010) to ensure that this 1990s punk-feminist movement of young women and their “noisy message of female empowerment” would be accurately remembered. Her research included interviews with more than 100 active participants in the subculture.

“I’d visit them with my tape recorder and Xerox all their zines from the box under their bed,” she said. “It was a wonderful, wonderful process.”

Readers still regularly write to her about the book, which was a finalist for the National Award for Arts Writing and has been translated into Polish, Portuguese, and Spanish.

“It's so gratifying to me that the book is still in print, it's still taught, and teenagers are still reading it,” she said. “It’s done better than I ever expected.”

Creating zines has some surprising similarities with authoring academic books and peer-reviewed articles, Marcus said.

“Being in conversation with a community of people who are invested in the same questions and whom you see once a year at a convention, the relative slowness of production, and the idea that you can share the beginning stages of your thinking as part of the process of building something bigger from it — Riot Grrrl was built on all these things, and so is academia,” she said. “I’ve pretty much re-created my punk feminist milieu from the ’90s.”

Marcus is now working on a new project, tentatively titled “Scarlet Records,” that examines the explosive development of popular music technologies and the spread of new ideas about gender roles from the 1890s to the 1930s.

As a graduate student, Marcus used to tell people that her dream job would allow her to combine English with music, gender studies, and creative writing.

“And that's what I've got,” she said with a smile. “Academia turned out to be the perfect place for the kind of thinker and writer that I am.”