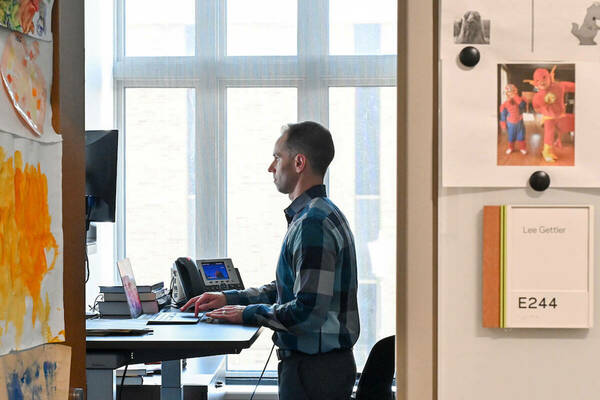

Notre Dame economics and French major Jaehyun Jung tries on traditional Korean clothing while conducting research in her native country last summer.

Notre Dame economics and French major Jaehyun Jung tries on traditional Korean clothing while conducting research in her native country last summer.

Jaehyun Jung spent the summer of her sophomore year interviewing Koreans who had lived through colonization, civil war, dictatorships, and democratization. It was not just a great academic experience, she says, it was also a personal journey. “I’m definitely even more proud of my heritage now.”

Jung’s research examining generational differences in Korean national identity was funded by a grant from the University of Notre Dame’s Undergraduate Research Opportunity Program (UROP). Offered through the College of Arts and Letters’ Institute for Scholarship in the Liberal Arts, UROP supports students pursuing a wide range of creative or research projects.

A native of Korea, Jung was inspired to pursue this line of research in part to better understand the distinct differences and similarities between the experiences and identity of her parents and grandparents. “When my parents were little, it was radically different from when their parents were little,” she says, “but Korea is very united in its Koreanness.”

The various generations of Koreans living today grew up in periods of dramatic—and sometimes violent—change, she says. “So if all these generations have lived such different childhoods and through such different times, how could they be so united in their Korean pride?” Jung asks. “It’s a fascinating question, and I wondered if I could document it before the older generations are gone and it’s too late.”

International Anthropology

Jung is a major in economics, has a supplementary major in French, and is pursuing a minor in anthropology, which taught her some of the research methodology and skills she drew on for this project. “With ethnography, you immerse yourself in the culture of your research subjects,” says Jung, “so I went to Korea to interview elderly and middle-aged people on their life histories.”

Professor Susan Blum, chair of the Department of Anthropology and a fellow at the Kellogg Institute for International Studies, served as a project mentor for Jung, helping her turn a very personal interest into a scholarly research project.

Jung initially expected the elderly generation, who are survivors of war and famine, to feel out of sync with the consumerist younger generation and current wealth of the Korean state. Surprisingly, she found just the opposite. “I think it’s because Korea has been united for so long, and Korean nationality is still based on ethnicity, everyone feels like we’re all part of the country.”

Among her interviewees were a woman who escaped North Korea by boat while the river around them was bombed, another who escaped through China, younger people who had been gassed in the streets while protesting dictators, and others who had never left Seoul but managed to survive through it all.

Jung found that for many, the war is a less traumatizing memory than other historical events. “They have more pain from being colonized and not being treated as real people in their own country,” she says. “The middle generation has many painful experiences with the police because if you just looked like a college student that made you look suspicious.”

Despite the difficulty of exploring such memories with her subjects, Jung loved the experience. “The participants told me really cool stories. They were so glad I was interested in my heritage and that I was doing this research with my school.”

Cultural Preservation

As part of the project, Jung developed a paper using the interview data to hypothesize the various reasons national unity remains so vibrant in Korea, and she is now considering turning one particular interview into a story or novel. “Starting the UROP project proposal was pretty scary for me,” she says, “but I pushed myself to take the opportunity, and it was definitely worth it.”

In fact, doing this research has helped clarify her future ambitions, she says. After graduation, Jung hopes to work for a non-governmental organization with a focus on cultural preservation.

“I feel like there are a lot of cultures that are really valuable but are at risk of disappearing because they happen to be less powerful in today’s global society,” she says. “If Korea was still poor, we could have been one of those cultures.”