There was a time when the size of the University of Notre Dame’s faculty and student body, the integrity of the University’s community, the enthusiasms of its students, and the very culture in which it was embedded all made it possible, in theater historian Mark C. Pilkinton’s succinct phrase, “for everyone to attend everything.”

For roughly the first half of Notre Dame’s history, work, study, prayer, meals, and leisure were all undertaken, endured, or enjoyed in a unanimity that is difficult even to imagine today.

Pilkinton’s new book, Washington Hall at Notre Dame: Crossroads of the University, 1864-2004, forthcoming from the University of Notre Dame Press, brings that time a bit more sharply into focus with two intertwined histories—one, of an iconic campus building and the other of theater at Notre Dame.

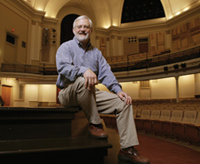

Pilkinton, a professor in the Department of Film, Television, and Theatre at Notre Dame, confesses at the outset that his interest in Washington Hall is “likely biased toward theater,” but the bricks and mortar in which theater and much else flourished on the University’s campus for more than a century and a half themselves tell the story of an institution, its people, and its culture.

Washington Hall at Notre Dame recounts several of these, including, inevitably, that of the ghost, which, according to legend, has haunted the building for nearly a century.

Honoring a promise exacted from him by Notre Dame’s emeritus president, Rev. Theodore M. Hesburgh, C.S.C., Pilkinton devotes an entire evocative chapter to this spirit whose first reported appearance shortly followed the death of the football player George Gipp.

With the fastidious agnosticism appropriate to his profession, Pilkinton attempts “neither to prove to believers nor disprove to skeptics” the ghost’s existence, but believers and skeptics alike will find much of interest in this excursion into local folklore. During the 1920s, for instance, Notre Dame students frequently violated a 10 p.m. campus curfew to hold all-night vigils in Washington Hall, hoping for a ghostly apparition.

One of those credulous insomniacs, a student named John Joseph Cavanaugh, would go on to become a Holy Cross priest and later Father Hesburgh’s immediate predecessor as University president.

Less credulous students, and later campus historians, have theorized that the ghost stories arose from a hoax perpetrated one December night in 1920 by a student named Joseph Casasanta, a talented trumpeter, assistant director of the Notre Dame Band and later composer of “Notre Dame Our Mother,” the University’s alma mater.

But among the other spirits pursued in Washington Hall at Notre Dame are what its author calls “the true ghosts…the fleeting shadows of myriad ephemeral events that have occurred over time.”

There are many of these to chase down. There have, in fact, been two buildings named Washington Hall at Notre Dame, the first of which Notre Dame’s founder, Father Edward Sorin, built in 1862 and demolished 20 years later to make way for the building that stands to the east of Notre Dame’s Main Building today. Even in choosing a name for the building, Father Sorin, whose Gallic temperament stirred an already fervently patriotic love of his adopted country, signaled an ambition to make an unmistakably Catholic university an unmistakably American one, too.

For most of the University’s history, the consequences of that ambition have played out in various ways on the Washington Hall stage. William Jennings Bryan, G.K. Chesterton, Henry James, and William Butler Yeats spoke to Notre Dame and to the world from there, as did Cardinal Eugenio Pacelli, shortly before he became Pope Pius XII, and New York Governor Mario Cuomo, then rumored to be running for president.

Sorin’s twinned commitments—to the Catholic faith and to the American nation—have become indelible features of Notre Dame’s institutional and communal life. Whether those commitments impossibly contradict or promisingly complement each other, Pilkinton’s study of a venerable campus building offers a valuable, provocative and perhaps indispensable view of them.