It sounds like an old joke in search of a punchline: “a biologist, an ethicist, and a priest walk into a bar.”

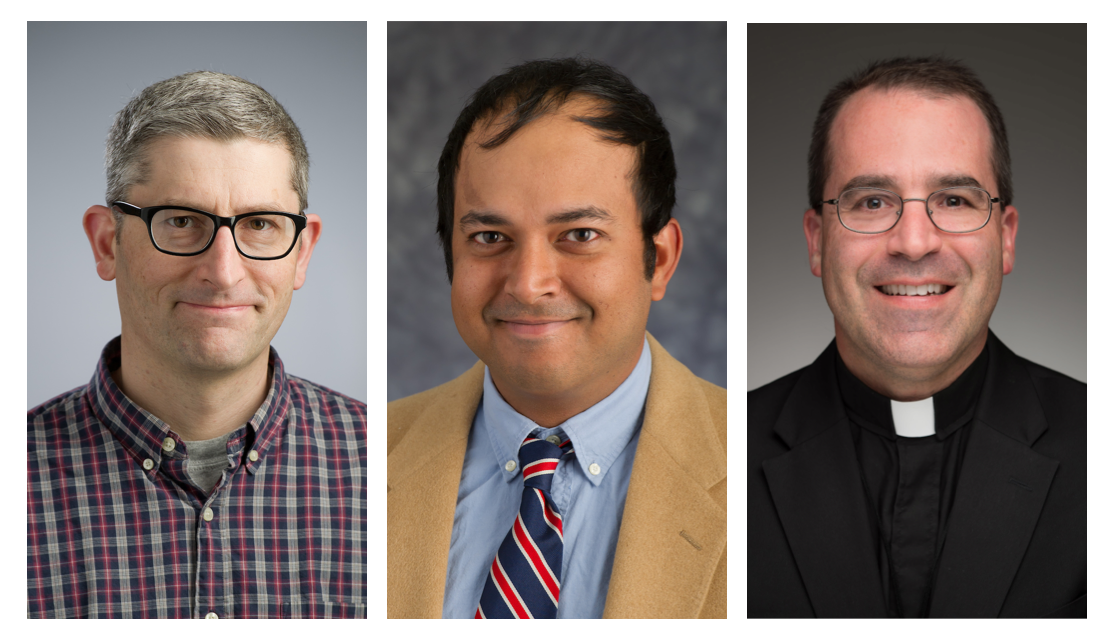

Except in this telling there is no bar and no adult beverages. Rather, the unlikely trio of Dominic Chaloner, Bharat Ranganathan, and Fr. Terrence Ehrman, C.S.C. walked into the offices of the Notre Dame Environmental Change Initiative (ND-ECI) at Innovation Park. The six-month research project that followed would prove enlightening, groundbreaking, at times challenging, and per Laudato si’, critical to the holistic thinking needed to save planet Earth.

“We’re really here to find the epistemological limits for each of our disciplines,” says Ranganathan, an ethicist and post-doctoral researcher on the project. “We want to create a new grammar that speaks across disciplines.”

The fact that a term like “grammar” means something different to an ethicist, than a biologist or theologian, reflects the Tower of Babel nature of interdisciplinary work. Yet that search for shared meaning was one goal of the project titled, “Theological and Environmental Ethics of Pacific Salmon in the Great Lakes.” It was co-sponsored by ND-ECI, Notre Dame Research, and the Center for Theology, Science and Human Flourishing (CTSHF).

The research sought to explore the principles of integral ecology set forth in Pope Francis’ 2015 encyclical Laudato si’ - “On Care For Our Common Home.” Among its key themes, the encyclical calls for “a broader vision of reality” that will attend to “both the cry of the earth and cry of the poor.” It is a focus that calls for comprehensive rather than one-dimensional thinking. Still, even at a collegial place like Notre Dame, it’s no small task to attain the unity across disciplines that Laudato si’ proposes.

“There’s this inertia about how a scientist should pursue these ideas,” said Chaloner, associate teaching professor in biological sciences, and director of undergraduate studies for the environmental sciences major. “People say, well, this [research] is all great but it doesn’t fit into any category. Where do I publish it? What if it’s something that our discipline doesn’t understand, and therefore sees as hokey or anathema?”

Chaloner, Ranganathan and Ehrman

Chaloner, Ranganathan and Ehrman

To avoid these potential pitfalls, the three researchers agreed on a tangible, locally relevant topic: the introduction of Pacific salmon into the Great Lakes.

It’s a saga that dates to 1966, when the Michigan Department of Natural Resources made a bold move to revive the depleted Great Lakes fishery. They stocked Pacific salmon in Lake Michigan to both control an explosion of non-native alewives, and replace native lake trout that had been decimated by invasive sea lamprey. Essentially, in this pre-EPA era, a handful of biologists were given carte blanche to re-engineer the world’s largest freshwater ecosystem — and, to do so with little regulatory or public oversight.

Financially, their biological roll of the dice paid off handsomely. As millions of salmon matured, they fueled a multi-billion dollar boom in boating, sport fishing, and tourism. Yet for better and for worse, the program also exemplified what Pope Francis calls the “technocratic paradigm” — a solution driven almost entirely by a scientific worldview, with little thought given to other social, cultural or ethical perspectives. Among them, that salmon can accumulate persistent organic pollutants, and pass these toxins on to humans and other creatures that eat them.

Now, Chaloner explains, the Great Lakes salmon numbers have plummeted. With ecological equilibrium restored, the native fish population has started to recover and Great Lakes resource managers now face a turning point.

“Simply stocking more salmon now isn’t going to change anything,” Chaloner said. “There’s not enough food for them in the Great Lakes. The alewives are all but gone. The money you spend (on stocking) won’t come back as full-grown salmon.”

For a scientist, the question of what to do next might begin and end with data alone. In contrast, by embracing an interdisciplinary approach, other elements enter the equation. And for that, Ehrman is an ideal candidate: he’s the rare priest with not only a Ph.D. in Theology, but a M.S. in Freshwater Ecology from Virginia Tech and a B.S. in Biology from Notre Dame.

“The Great Lakes aren’t anyone’s possession,” Ehrman said. “So how do we view them as a common good, and not just for humans, but for all creatures? We have dominion over these things, but how do we use them for our necessity and not for our greed? How to care for the earth is intrinsic to being a disciple of Christ.”

The so-nicknamed “Ethics and Ecology” project began in 2016 when Chaloner and Ehrman applied for a Faculty Research Support Grant from ND Research. They first planned to hire an ethnographer, who would interview stakeholders such as scientists, natural resource managers, clergy, tribal leaders — even charter boat captains and fishermen and women who consume Great Lakes salmon. This input would provide the basis for a paper and subsequent policy recommendations.

Then with seed funds from ND-ECI and CTSHF, they brought Ranganathan aboard in summer 2017. He’s a religious ethicist with a deep affinity for animal and bio ethics. Ranganathan convinced the group that they’d missed a step. They hadn’t listened closely enough to understand each other’s point of view. Until they did, how could they expect other researchers and stakeholders to do the same?

“It was a steep learning curve, but it’s the kind of messiness that fosters interdisciplinary creativity,” Ranganathan said. “It calls for radical humility. You’re going to have the principles that you’re comfortable with challenged.”

No one expected that each would become experts in the other’s fields. Instead, they read common articles that dealt with creation care, faith, and science. Along with the vision provided in Laudato si’, they also found a pastoral letter by Catholic bishops from the United States and Canada about the Columbia River Watershed to be helpful, as were the writings of Professor Peter Vitousek, an ecologist at Stanford University. For Ranganathan, Dan Egan’s “The Death and Life of the Great Lakes,” provided an essential over view.

“It’s about getting the new vision that Pope Francis talks about,” Ehrman said. “We have to move from our piecemeal knowledge, to a broader vision of wisdom about the world.”

This meant that in conversation, the three couldn’t just lobby or default to their own specialties. They had to develop the common grammar that Ranganathan described earlier – a means to merge their ideas into a broader whole. It’s a style of dialogue that they jokingly refer to as “salmon Esperanto.”

From there, the team developed a cohesive proposal and will now seek support from private foundations to support the next phases of work. This includes the addition of an ethnographer to conduct interviews, analyze the findings and develop a framework to guide public discussions about issues such as Great Lakes salmon or climate change. The team’s goal is to have the project conclude with a Notre Dame conference on public engagement in the spirit of Laudato si’.

For those seeking the challenge (and unanticipated gifts) of true interdisciplinary work, Chaloner, Ehrman, and Ranganathan cite three lessons learned that they found helpful:

Start with someone you know: To hedge your bets for interdisciplinary success, it helps to have some prior connection with fellow researchers. Ehrman knew Chaloner, and was in the same undergrad class as Dom’s wife, Kristin Lewis (Science Pre-Professional ’91). Ranganathan was a fellow with the Notre Dame Institute for Advanced Study in 2013—2014, and the Notre Dame Center for Ethics and Culture in 2014-2106. He still has good friends on campus.

Don’t let expert knowledge stifle discourse: Never assume that a priest, farmer or teacher can’t contribute to scholarship on a given topic because they lack a proper credential. In conversations bogged down by conventional thinking, an outside perspective can be groundbreaking. As Zen master Shinryu Suzuki once said, “In the beginner’s mind there are many possibilities; in the expert’s mind there are few.”

It pays to invest in dialogue: While researchers may welcome the chance for interdisciplinary dialogue, they still need financial incentives to make time for it. Otherwise, competing demands for teaching and other research will take priority. Investing in shared conversations is a crucial building block for innovations that may not develop in any other way.

“Here’s the punchline: talk is cheap,” Chaloner said. “But if you structure an interdisciplinary conversation in the right way, it can be more valuable than anything.”

Originally published at environmentalchange.nd.edu.