Life is full of coincidences that in fiction would seem incredible.

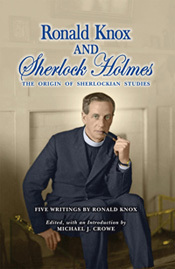

The story of Michael J. Crowe’s new book, Ronald Knox and Sherlock Holmes: The Origins of Sherlockian Studies (Wessex Press) has a startling number of coincidences—and just as many unlikely University of Notre Dame connections.

The story really starts more than 35 years ago, a time when there was a local Sherlock Holmes society, “The Solitary Cyclists.”

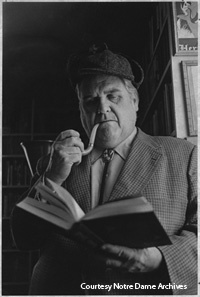

Crowe, the Rev. John J. Cavanaugh, C.S.C., professor emeritus in Notre Dame’s Program of Liberal Studies and an expert in the history of the physical sciences, was a founding member and a dedicated Sherlockian (a devoted fan of or an expert on the adventures of Sherlock Holmes).

A Chance Meeting

One day Crowe got a letter from a 15-year-old boy who wanted to join the group. Steven Doyle’s father was stationed at Notre Dame teaching in the Air Force ROTC program, and Doyle, who’d received a matched set of the Sherlock Holmes stories for Christmas, wrote a letter to the group’s contact—Michael Crowe. He received a handwritten note from Crowe, addressed to “Mr. Doyle,” inviting him to join and noting that annual dues were $2.

“Then I had a sudden fear—oh gosh, they don’t know I’m a kid,” Doyle recalls. “I wrote again and fessed up. He wrote back and said it would be okay.” Doyle doesn’t remember much about that first meeting, only that he wasn’t yet old enough to drive, and his father had to drop him off.

Doyle attended the group for a year or so, until he got a little older, acquired his first car and developed an interest in girls. Doyle’s role in the early part of the tale ends here—but he will return at the end of our story.

Enter the Monsignor

At one of those meetings of the now-defunct “Solitary Cyclists,” Crowe had presented to the group a memorable essay he had written on Msgr. Ronald Arbuthnott Knox (1888 to 1957), a convert from Anglicism who at one time was said to be “the most celebrated Catholic priest in England.”

Today, says Crowe, the only people who have heard of Knox are “over 70, Roman Catholic and well-read.” But Knox was well known in the early 20th century for his translation of the St. Jerome Vulgate Bible into English, and wrote many works of Catholic apologetics.

Like his peer and friend G.K. Chesterton, Knox also wrote detective novels—several of which (The Viaduct Murder, The Footsteps at the Lock) are still in print. Along with Chesterton, Agatha Christie and Dorothy Sayers, he helped found the Detection Club, and created a “10 commandments” of sorts for writers of detective novels, including: “No accident must ever help the detective, nor must he ever have an unaccountable intuition which proves to be right.”

“Higher Criticism” of Sherlock Holmes

The witty Knox (who, biographer Evelyn Waugh noted, was remembered at Eton as “the cleverest boy who ever passed through that school”), had been interested in Sherlock Holmes from the time he was a boy. In 1911, he wrote a satirical essay “Studies in the Literature of Sherlock Holmes.”

At the time, “higher criticism” of the Bible was in vogue—a form of literary analysis that focused on the sources of documents. In his essay, Knox mockingly described in the lofty terms of literary criticism the structural elements of a Sherlock Holmes tale: Exegesis kata ton diakonta (“client’s statement of the case”) and the Anagnorisis, wherein the apprehension of the villain takes place.

The essay was read to societies in Oxford and London, and was read by Arthur Conan Doyle himself. Thus Knox is credited with creating from whole cloth the notion of “Sherlockian studies”—called “The Grand Game” by generations of loyal fans—treating Sherlock Holmes as if he actually existed, and Conan Doyle’s stories as based on historical fact.

Conan Doyle wrote to Knox in 1912, expressing his amusement—and amazement— at the essay. “That anyone should spend such pains on such material was what surprised me. Certainly you know a great deal more than I do, for the stories have been written in a disconnected (and careless) way, without referring back to what had gone before.”

Lost, Found—and Published

Michael Crowe’s essay on Knox was never published—it contained an unpublished letter from Arthur Conan Doyle to Knox he didn’t have permission to print. But he did give one copy to friend and 1937 Notre Dame graduate John Bennett Shaw, cautioning him that he must never show it to anyone else.

Shaw (1913 to 1994), whose 2,000-volume G. K. Chesterton collection and 2,000-item collection of the work of English engraver and typographer Eric Gill are held in the Hesburgh Libraries, also amassed one of the world’s largest collections of “Sherlockiana.”

The collection was eventually transferred to the University of Minnesota, where physician and Sherlock Holmes aficionado Dr. Richard Sveum located a copy of Crowe’s unpublished essay and wrote to him, suggesting that he publish it and perhaps turn it into a book.

The Return of Steven Doyle

Sveum put Crowe in touch with specialty publisher Wessex Press, the premier publisher of Sherlockiana in the world. Crowe contacted the press co-director who (plot twist!) is revealed to be none other than Steven Doyle, whom Crowe had last met as a 15-year old high school student. Crowe updated the essay as the introduction to Ronald Knox and Sherlock Holmes, which includes Knox’s “Studies in the Literature of Sherlock Holmes.” The book was published just in time for the 100th anniversary of the original presentation of Knox’s essay.

In Crowe’s introduction to the book, he notes that Knox complained about his fame as the purported inventor of “The Grand Game.”

“The sad irony,” Knox wrote, “is that my one permanent achievement was setting the groundwork for all the Sherlockians that followed.”

Crowe and Doyle will discuss Crowe’s book at 7:30 p.m. on Tuesday, March 1 in the Hesburgh Center Auditorium. The lecture is free and open to the public, with a reception to follow. After the talk, Crowe will autograph copies of his book; Doyle also will be available to sign copies of his recent book Sherlock Holmes For Dummies.

Learn More>

- Michael J. Crowe faculty page

- Ronald Knox and Sherlock Holmes: The Origins of Sherlockian Studies

- Program of Liberal Studies

Originally published at newsinfo.nd.edu.