Jaime M. Pensado

Jaime M. Pensado

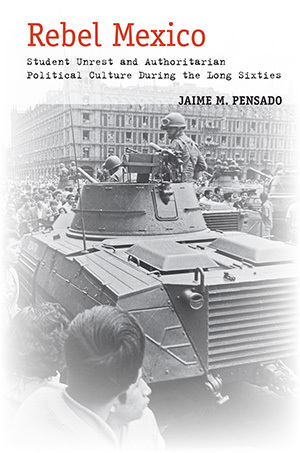

Notre Dame historian Jaime M. Pensado has been awarded the Conference on Latin American History’s 2014 Mexican History Book Prize for his first book, Rebel Mexico: Student Unrest and Authoritarian Political Culture During the Long Sixties.

An unprecedented look at student activism in 1960s Mexico, the book was judged to be the most significant work on the history of Mexico published in 2014. Pensado accepted the prize in January 2015 at the American Historical Association’s annual meeting in New York City.

“It is the award for Mexico’s history and, in that sense, I’m humbled and very honored to receive the award,” said Pensado, the Carl E. Koch Associate Professor of History. “It’s nice to be recognized.”

Discovering New History

Rebel Mexico

Rebel Mexico

Like many areas around the world, Mexico was experiencing turbulent times in the 1960s. Student unrest over government violence and suppression culminated on Oct. 2, 1968, in the Tlatelolco plaza of Mexico City, when military and police forces killed dozens of student protestors and civilian onlookers.

“Mexico—just like Paris, Tokyo, Berkeley, Columbia—had huge student uprisings, Pensado said. “But what made Mexico unique was that the student movement ended very tragically.”

For decades, Mexico’s history was limited, as the government restricted access to documents and other resources. But in 2000, when the National Action Party secured the presidency, Mexico’s National Archive was opened to the public for the first time in more than 70 years.

That decision reshaped Pensado’s research—and fundamentally altered perceptions of modern Mexican history.

While working at the National Archive, Pensado discovered a series of files labeled “student problems.” He soon realized the government had started gathering intelligence on activists as early as 1956—12 years before the massacre at Tlatelolco.

Previously, student activism in Mexico was portrayed as a brief occurrence, with a singular focus on 1968, but it was the much longer history that intrigued Pensado.

The “long sixties”—the period from 1956 through the 1970s—is when “the student, as an actor in society, became a problem for the nation,” Pensado said.

Using newly uncovered accounts from student newspapers and government reports, Pensado identified and interviewed some of the “agent provocateurs”—individuals employed by the government to suppress, incite, and divide students—that were used throughout the long sixties.

Until now, historians had presented the Tlatelolco massacre as emblematic of a “monolithic superpower,” but Pensado found that depiction to be far from accurate.

In Rebel Mexico, Pensado argues that the events of 1968 were not a momentary display of the government’s power, but were actually the result of weakness within government stemming from longstanding internal conflict.

“Because of the fractures within the state, the state was incapable of negotiating the very meager demands by the students,” he said. “The history is more complicated than we tended to think. I trace that longer history.”

Enabling New Voices

Pensado hopes that, like Rebel Mexico, his subsequent research can help provide a voice for those who have been marginalized in the official history of their country.

“There are so many different angles that we still have to study,” he said. “For that to happen, we have to move away from the official narrative.”

Pensado is already working on his next book, which aims to examine the ways young Catholics in Mexico participated in and reacted to social movements of the 1950s and ’60s.

Though his work is focused on events from a half-century ago, the narrative he presents remains relevant today, he said.

Protests and unrest followed the disappearance of 43 students from a college in southern Mexico in September 2014. A government investigation, concluding the students were killed by a local crime organization, failed to satisfy a significant segment of the public.

“There’s a huge social movement right now in response to the disappearances,” Pensado said. “That movement keeps growing, and it’s primarily led by young people.”

For Pensado, the similarities between the past and the present are striking.

“Rebel Mexico, to some extent, explains the ways in which the state is trying to handle this latest student uprising,” he said.