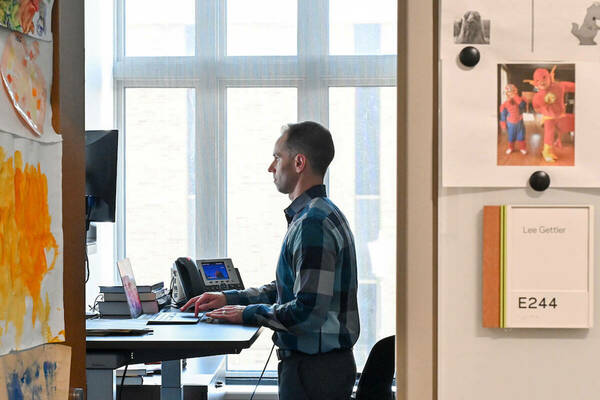

Larissa Fast

Larissa Fast

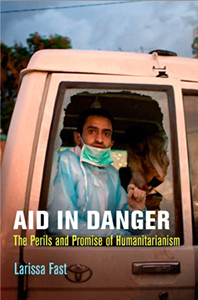

The title of Notre Dame sociologist Larissa Fast’s new book, Aid in Danger, has a double meaning. The first is that humanitarian workers around the globe are at greater risk than ever of being attacked, injured, kidnapped, or killed.

The second is that as aid agencies provide increasingly sophisticated security for workers—often isolating them from the populations they serve—they risk compromising the essence of humanitarian aid: a relationship formed when one human being relieves the suffering of another.

In Aid in Danger: The Perils and Promise of Humanitarianism (University of Pennsylvania Press), Fast tackles these intertwined challenges and offers a pathway for reforming the system.

“Aid workers are attacked for all kinds of reasons,” said Fast, assistant professor of conflict resolution at the Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies. “They could be attacked because of their ethnicity, their possessions, the politics of the conflict—or they might be simply be caught in the crossfire.”

Attacks against aid workers have been steadily increasing since researchers began tracking them in the 1990s, said Fast, whose book is based on field research in Palestine and South Sudan and hundreds of conversations with aid workers and nongovernmental security officials.

Reasons for the increase range from better reporting of attacks to higher numbers of aid workers worldwide. Many humanitarian organizations have blamed attacks on external factors, responding with bolstered security for workers, housing them in guarded compounds, instituting curfews and taking other measures that increase separation between aid workers and populations needing assistance.

“These protective measures are important, but they also create psychological and physical barriers,” Fast said. “If aid workers can’t get out and interact with the people they are supposed to be serving, it detracts from the quality of the assistance.”

As an alternative to an aid model that normalizes danger, fear, and separation of aid workers from the populations they serve, Fast urges aid organizations to balance security concerns with efforts to foster trusting relationships among aid workers, those they serve, and local officials.

“This is not an argument for naïve security-management policies,” Fast said. “It’s a call for an approach to humanitarianism and security management that keeps human relationships at the core.”

Aid in Danger is “one of the very few evidence-based, well-researched, and eminently readable studies of the field,” said Peter Walker of Tufts University’s Feinstein International Center. “This should be on the ‘must-read’ list of every researcher, head of operations, and security director working with humanitarian aid in conflict zones.”

The book “makes a compelling case that a relational, humanity-based approach to thinking about security will generate behavior and outcomes more consistent with the principles on which humanitarianism rests,” said Deborah Avant of the Josef Korbel School of International Studies at the University of Denver. “This is a book that should be read by students and scholars of aid as well as by practitioners.”

Larissa Fast earned her Ph.D. from the Institute for Conflict Analysis and Resolution at George Mason University. Her research focuses on violence against civilians intervening in conflict, such as aid workers and peacebuilders. She also is interested in humanitarian politics, development and conflict, evaluation, and peacebuilding. Fast has consulted and worked for international organizations, primarily in North America and Africa.

Fast’s research has been funded by the United States Institute of Peace, the United States Agency for International Development, and the Swiss Development Corporation. She also is the author of numerous articles documenting and analyzing the dangers of civilian intervention in violent conflict around the world.

Originally published at kroc.nd.edu.