Every democracy is a work in progress. The degree to which some succeed and others fall short is at the heart of what sociologist Robert Fishman explores in his research and teaching at Notre Dame.

“The whole idea of democracy is premised on the principle that all citizens should be equal politically—and that is a very hard standard to fully attain because the societies in which democracy exists are all settings of inequality, to a greater or lesser extent,” Fishman says.

“I’m interested in explaining the variations from one case to another.”

Comparing Societies

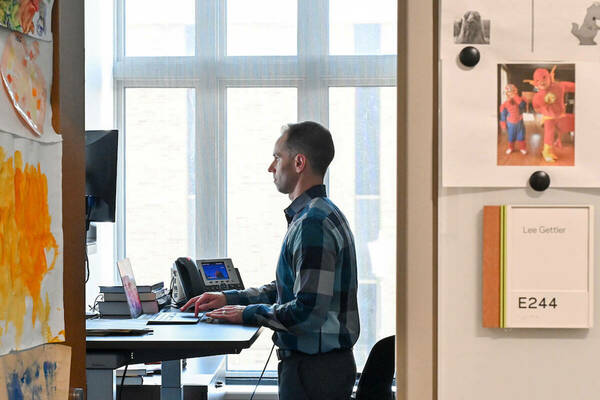

A faculty fellow at the University’s Kellogg Institute for International Studies and Nanovic Institute for European Studies, Professor Fishman is currently analyzing differences in the democracies of Portugal and Spain.

The two nations have a long history of structural and cultural similarities, he says, but they diverged in important ways in the 1970s—a time that began what is often called “the third wave” of democracy.

“It is important not only to compare societies in the context of individuals but also to examine systematic differences that can only be observed at the aggregate level,” Fishman says. “Historical processes take different forms; those who study only one country sometimes assume those processes are universal.

“It is only by comparing societies that we are able to understand how particular historical processes shape outcomes.”

Examining Inequality

Fishman, who joined Notre Dame’s College of Arts and Letters in 1992, grew up in Appalachia, West Virginia, where poverty and inequality were—and still are—quite pronounced. Later, he lived in Spain, initially in the spring of 1973, when the country was governed by a dictatorship.

“I saw people in the streets bravely demonstrating in favor of democracy and experienced the transition to democracy, so that influenced and sensitized me to the issues that I have investigated as a scholar,” he says.

Among the questions Fishman now explores is why there are significant differences from one country to another when it comes to treating low-income people as political equals in the democratic conversation.

“To be quite direct, the United States is not an ideal case from this standpoint. Most politicians typically pay very little attention to the opinions and preferences of low-income people.

“My view,” he says, “is that certain social and cultural processes have enormous consequences in allowing poor or low-income people to occupy a place at the table of conversation.”

Connecting with Students

In the classroom, Fishman enlivens his research by connecting it to his students’ interests. For example, in a first-year seminar called Understanding Democracies, he shares with students how differences in the way democracies function can lead to differences in unemployment rates or even the kind of music people prefer.

“When I mention those two points, I can see that it helps students understand in their own lives what could be the meaning of the principles and theoretical dynamics we focus on in class.”

Working with his graduate students, in turn, Fishman is able to focus more deeply on each individual student’s longer-term research interests as well as the process of more in-depth research itself.

“I’m a great believer in the idea that teaching is not only about transmitting information but also about helping students build their own critical capacities,” he says. “If a professor is to do that, he or she needs to pay a lot of attention to what the interests of students are.

“Teaching involves a lot of preparation but also improvisation.”

Provoking Interest

In exploring his own research interests outside the classroom, Fishman has published several books, including The Year of the Euro: The Cultural, Social, and Political Import of Europe’s Common Currency (2006); Democracy’s Voices: Social Ties and the Quality of Public Life in Spain (2004), which earned an honorable mention in the best book in political sociology category from the American Sociological Association; and Working-Class Organization and the Return to Democracy in Spain (1990).

More recently, Fishman particularly enjoyed the reception of his 2011 op-ed on the Portuguese bailout that was published by The New York Times. The piece sparked wide-ranging interest from abroad and also led quickly to invitations for Fishman to speak, to be interviewed, and to write other pieces. “A career is a process of growth and of interaction with others in which one hopes to make an influence, and so that experience was especially moving to me.

“With scholarly publishing, it is unusual for one’s work to have that kind of immediate impact,” he adds. “I don’t suggest an op-ed is more important than scholarly work, but the response I received, especially from Portugal, was personally very rewarding.”