Anyone who has been through an ordeal with cancer knows firsthand that the disease, related stressors, and subsequent treatments take a toll not only on the body but also on the mind.

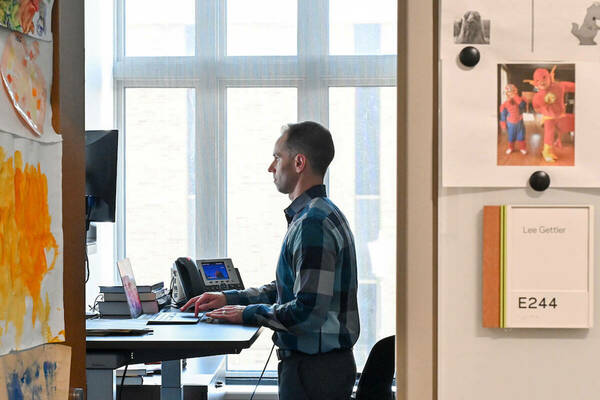

Pascal Jean-Pierre—who this fall was named assistant professor of psychology and Walther Cancer Foundation Collegiate Chair in Psychology at the University of Notre Dame—has spent a good portion of his career advancing cancer-control research and working to improve psychosocial functioning and the quality of life for cancer patients and survivors.

“I have always been fascinated by the complexity of the human brain-behavior relationship,” Jean-Pierre says. “I am especially interested in understanding and finding ways to facilitate neuroplasticity and the brain’s ability to recover its functions in the context of cancer and its treatments such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and hormonal therapies.”

Coping With Cancer

Jean-Pierre comes to Notre Dame from the University of Miami Leonard Miller School of Medicine, where he was assistant professor of radiation oncology for two years. He also facilitates research collaboration as an adjunct professor of radiation oncology at the University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry, where he completed his postdoctoral studies under the mentorship of Gary Morrow ’66.

At Notre Dame, he is now developing the Neurocognitive Translational Research Laboratory and the Cancer Control Research Program. He is collaborating with colleagues from various fields of study at Notre Dame, the Harper Cancer Research Institute, Indiana University School of Medicine South Bend, and other community institutions, hospitals, and cancer clinics.

According to Jean-Pierre, the new lab will focus on developing and implementing research strategies to identify and describe the causes of CRND, or cancer and treatment-related neurocognitive dysfunction.

This condition, he explains, “refers to problems in the brain and its functions—such as being unable to focus and pay attention, remembering information, and planning and carrying out routine activities of daily functioning—as a result of having cancer and/or having received cancer treatments.”

Other areas of research will include cancer- and treatment-related problems such as fatigue, anxiety, and depression. “Cancer and its treatments can exacerbate psychological issues for patients and survivors,” Jean-Pierre says. “And psychological issues such as anxiety and depression can also confound other issues.”

Eliminating Disparities

Jean-Pierre is also interested in strategies to eliminate cancer-care disparities for individuals from disadvantaged populations.

“Those disparities,” he says, “include the inability to access equitably beneficial cancer-related care including screenings, treatments, and follow-up visits, as well as timely access to cancer treatment for individuals from medically underserved and lower socioeconomic groups and for people living in geographical regions where reliable cancer-care facilities are not readily accessible.”

To help address these concerns, Jean-Pierre has been working with the Patient Navigation Research Program funded by the Center to Reduce Cancer Health Disparities of the National Cancer Institute and the American Cancer Society. These efforts have included developing and psychometrically validating bilingual measures of Patient Satisfaction with Cancer-related Care (PSCC) and Patient Satisfaction with Interpersonal relationships with Navigators (PSN-I)—those who help them navigate the healthcare system.

Teaching and Learning

Jean-Pierre says his decision to pursue postdoctoral training and eventually become a researcher and teacher was influenced by his search for literature about cancer treatments and side effects to help friends and relatives diagnosed with cancer.

“I think we’re learning more about the brain and its function, especially following insults such as cancer and its treatments,” he says. “We’re learning about possible pharmacological or behavioral interventions that may show promises, which may then be tested across other clinical populations and vice versa.”

During spring 2013, Jean-Pierre will teach undergraduates in the College of Arts and Letters a course called Health Psychology: Theory, Research and Practice. He is planning another course on Applied Behavioral Medicine/Oncology for the following semester.

Because a third of psychology majors are also pre-med students, he says, his courses are designed to be interdisciplinary.

“I am hoping a mixed group of students majoring in psychology, pre-med—and other disciplines—will find my courses relevant and actively participate in the course lectures and activities.”