The European Union received the Nobel Peace Prize—despite current economic woes and social unrest—for transforming most of Europe from “a continent of war to a continent of peace.”

But political scientist Joshua Bandoch, who received his Ph.D. at Notre Dame this year, argues that the 27-member-nation European Union is trying to form too close of a union. “This is problematic because the diverse peoples of this union are more different than their leaders seem to want to acknowledge.”

Now a post-doctoral fellow at Brown University’s Political Theory Project, Bandoch discusses the matter in a chapter entitled “On the Problem of Forming a European Spirit—Montesquieu’s De l’Esprit des lois (1748)” in the recently released Ideas of | for Europe: An Interdisciplinary Approach to European Identity.

Political Particularism

Bandoch says he began to focus on Montesquieu after learning how many luminaries the 18th century political philosopher influenced, including Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Adam Smith, G.W.F. Hegel, Alexis de Tocqueville, and America’s founding fathers.

“I came to appreciate Montesquieu not only as a deep thinker in his own right,” he says, “but, more importantly, I came to see him as a political theorist who has a lot to teach us about contemporary politics. And I firmly believe that political theory must be able to speak to contemporary politics.”

Based on a new interpretation of Montesquieu’s political thought, Bandoch’s doctoral dissertation argued for an approach to political theorizing called “political particularism.” His current book project offers an extended philosophical and historical analysis of this concept.

“I define political particularism as the idea that political, economic, social, and moral factors need to fit a particular people while at the same time advancing security, liberty, and prosperity,” he says. “Societies vary widely in all of these areas, and political particularism takes these differences as a given and works to discern the best way to (re)shape societies, knowing that the final product should differ across time and place.”

According to Bandoch, scholars typically try to identify what Montesquieu thought was the best form of government and assume he wanted all societies to strive for that. “This misses Montesquieu’s point, which is to figure out what best fits the nature of each society.”

Scholars in Training

Looking back at his graduate work at Notre Dame, Bandoch says it “prepared me better than I could have hoped for to be ready to make important contributions with my teaching and my research.”

Part of what stood out about his experience as a Ph.D. student was the nurturing intellectual environment of the Department of Political Science.

“You hear terrible stories about grad school, about the cutthroat atmosphere in which students see everything as a zero-sum game,” he says, “but Notre Dame was the opposite.”

The practical and financial support he received was also critical to his success, Bandoch says, pointing to more than 15 fellowships, scholarships, and grants he received, some of which allowed him to spend a full year conducting research in France.

It was while doing research at the Municipal Library of Bordeaux that he rediscovered documents in which Jean-Jacques Rousseau comments on Montesquieu’s ideas about the equality of the sexes.

“In the manuscripts, Rousseau seems to suggest that Montesquieu did not go far enough in advocating for the equality of women,” says Bandoch, who is now working with Notre Dame Associate Professor of Political Science Eileen Hunt Botting to produce an article on his findings.

From Research to Teaching

“I think Josh will make a major contribution to the history of ideas with the analysis of these manuscripts,” Botting says of her former student. “His postdoctoral fellowship at Brown University’s Political Theory Project is also a testament to the quality of his research trajectory and his commitment to excellence in undergraduate teaching in the liberal arts.”

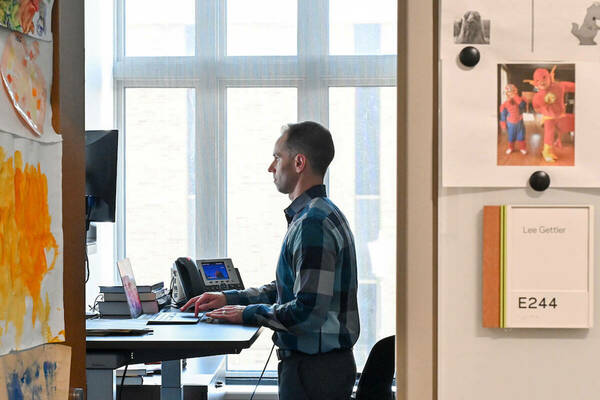

At Brown, Bandoch is co-teaching an interdisciplinary class called Prosperity that considers what it takes for a society to be free, fair, and prosperous from historical, political, economic, and philosophical perspectives. He is also teaching a first-year seminar about different conceptions of freedom.

“I chose to pursue a career in political science not only to have the opportunity to think deeply about the world,” he says, “but to help students learn to do so as well.”