It used to be that if you weren’t at home or work, your voice on an answering machine was the closest people could come to talking to you.

Cellular phones, however, have drastically changed the communications landscape, turning airport layovers into business opportunities, solo trips to the store into collaborative shopping efforts.

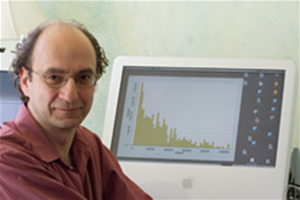

“The major reason for studying mobile telephone networks has to do with increasing our understanding of social networks and their importance in society,” says David Hachen, associate professor of sociology. “Communication networks are one of the most important types of social networks.”

Hachen has teamed with Notre Dame faculty members Albert-László Barabási (Physics) and Gregory Madey (Computer Science and Engineering) to work on a project known as WIPER, which is supported by a three-year grant from the National Science Foundation.

WIPER’s main goal is to develop a response system that identifies emergencies by detecting anomalies in cell phone usage. The idea is that a sudden, significant deviation from normal calling patterns concentrated in a particular location would indicate something out of the ordinary was happening there.

So how do you figure out what constitutes “normal”?

You study the habits of over seven million people.

“This is a very rare, very extensive, very complicated, and very confidential data set that allows us to map out social networks in a way that has never been done before,” says Hachen, a co-principal investigator on the project.

Through an agreement with a cellular phone provider, the team has access to information such as the number of times subscribers call or receive a call from someone, how long their calls last, text message usage, and when and where each call is made.

Making these records available raises inherent security concerns, meaning Hachen and his colleagues must take numerous precautions in their work.

They cannot disclose the cell phone provider or the country from which they are pulling the data. Every phone number is encrypted, and Hachen stresses that they know very little about the callers themselves—only basic demographic characteristics like age, sex, and contract type—and nothing about the content or purpose of any call or message.

His current work focuses on the amount of time different groups of people spend speaking on their cell phones. Preliminary findings indicate that women talk more than men, even though men have slightly larger networks of people with whom they communicate. The number of people a person talks to tends to decline with age, but the frequency of their conversations increases.

“The data we have are ‘real’ data, not people’s reports of what they did, but actual records of what they did,” Hachen says. “The science of networks has been rapidly developing in the last decade, and these data can help us answer important questions about how networks operate.”